The old man had a favorite painting in his little wooden hut. It was a beautiful seascape. The man loved and connected with it, beginning with the nice touch of the thin line of frayed rope stitched into an otherwise ordinary and simple wooden frame. He would stare at the painting when his heart was heavy and be lifted by the movement of the waves crashing against the rocks and along the shore―how expertly done! He’d feel the soft pink and yellow tones that came through the clouds and lit up the cresting waves and it warmed him. Sometimes he’d imagine it as a sunset and sometimes he’d imagine it as a sunrise. It depended on the day. Above all, he liked to watch the seagulls that drifted lazily in the ember light, above the sound of the sea.

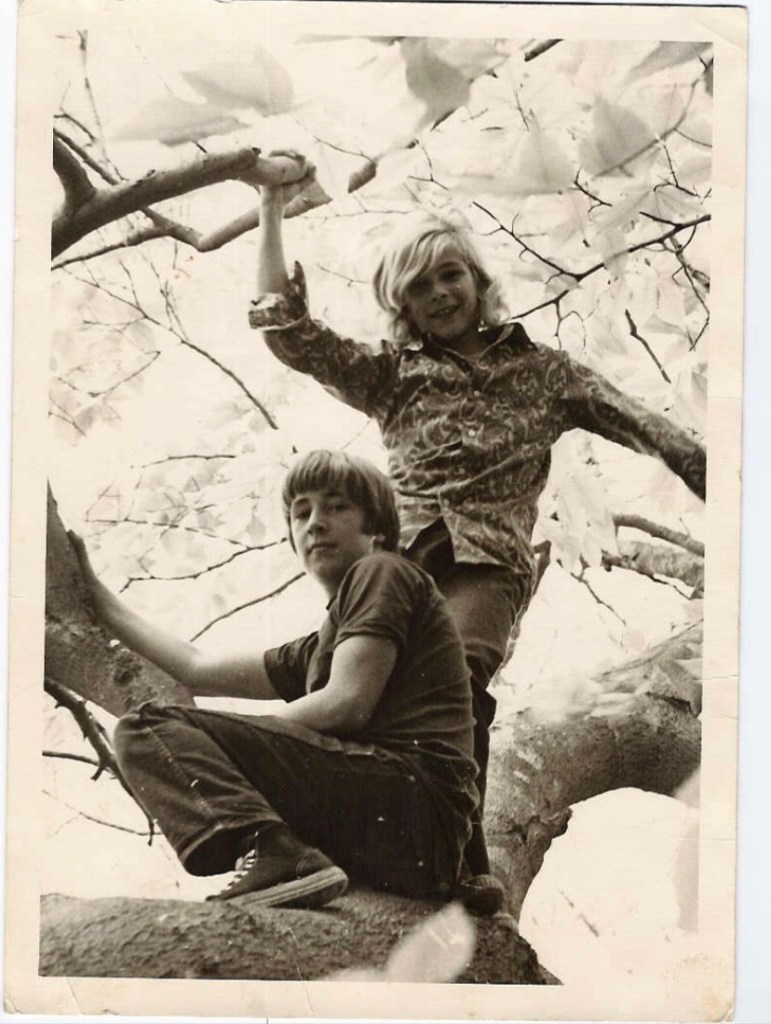

He had two grandchildren, a wonderful little girl and boy, and they loved the painting too. They would all joke about seeing the seagulls move slightly in the painting from time to time, depending on the breeze, and would even declare that one or more seagulls had flown away or flown into the picture making the number of seagulls in the sky greater or lesser. They’d announce that the sound of the waves was especially loud today, and they’d all laugh. He’d remember the times they spent at the seashore, and all the times they’d spend together reading stories at bedtime or playing in the autumn leaves, or building forts with lincoln logs, and love always glowed among them in soft pink and yellow tones.

He was looking at the painting now and thought of that difficult time when he moved from their big house into the small hut where he now resides. When the children first visited after the move he pointed at the painting and asked them if any seagulls had left the scene or whether the waves were quiet or loud today. The children barely looked at the painting and grew quiet. He asked what was wrong and finally they said “Mom says the painting is ugly.” The old man was stunned, and gently tried to tell the children that their own experience of the painting is more true than another’s, being careful not to cast Mom in a bad light. Being children, they didn’t fully understand the ways of the world, but they are wonderful children, and the old man always understood this and so he was patient and loving. He was sure that this was a passing moment. But it wasn’t, and the children were allowed to visit less and less until they couldn’t visit at all or even speak to him. The old man’s soul was crushed and the unhappiness of the whole situation was thoroughly alien to him.

For years, the old man has been trying everything within his power to get the children to see the painting as it is, and not as another says it is, but so far he’s been unsuccessful due to contrary and overwhelming messaging coming from another. He has learned how difficult it is for children to see the truth sometimes, especially when forced to choose among those they love. He loves the children as much as ever and thinks of them always.

Always.

Always, he held the children like an ember in his heart and thought “Someday they will see, someday they will see.”

And one day, they did.

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.