I once had a Prince throw a feast for me. I know this has probably happened to all of you too, but I’m still going to tell you about it! I’m thinking back on it now that it seems like the U.S. military is leaving Afghanistan for real in a few months. Indeed, the drawdown of U.S. forces and equipment is already operational. A jumble of images surface over this, things I saw during my deployment to Afghanistan in 2007-2008.

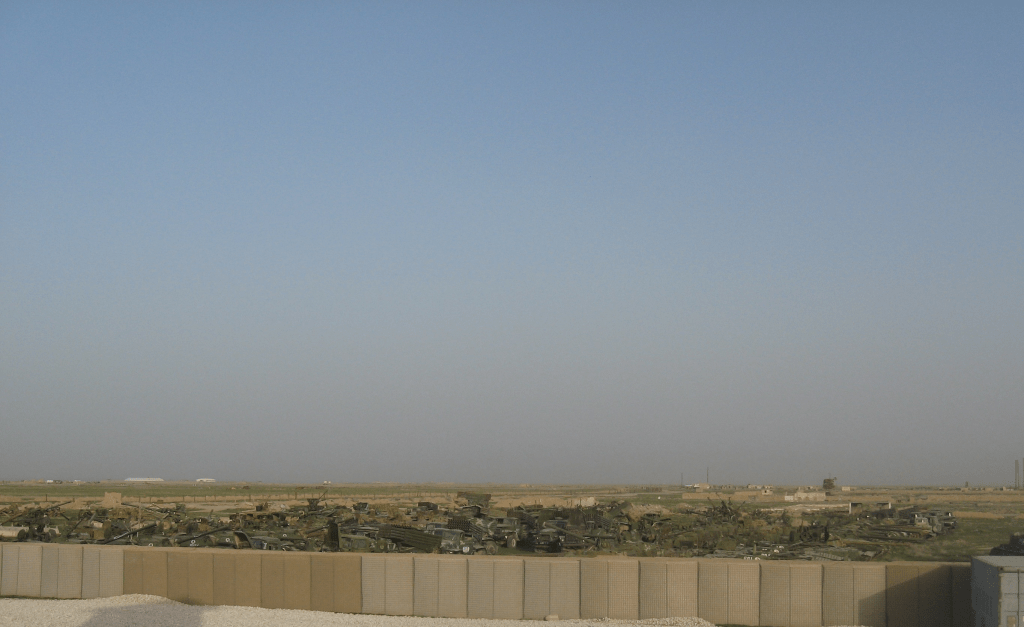

Russian military equipment was everywhere. Wrecked tanks, wrecked mobile weapons systems, and damaged armored vehicles of all sorts dotted the roadsides and indeed gathered in great numbers at some of the more prominent bases. My first post (or COP, for Combat Outpost) was in Konduz Province and we had an impressive array of such damaged vehicles at our location. I never then considered the blood and gore that must have painted the insides of every one of these vehicles. Sometimes at night I would walk through the boneyard and feel the great Russian presence amid the angry twisted hulks, the silence, and the shadows.

It was now the Spring of 2008 and the Americans are here, in great numbers and with substantial Coalition Force backing. Though the Americans were the predominant force, we coexisted in my region with Germans, Swedes, Norwegians and Croats. By this time, all of our HMMV vehicles were ‘up-armored’ and we were even receiving pretty much blast-proof vehicles for transport–a whole family of Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAPs) vehicles were starting to appear ‘in theater’. We had astonishingly overwhelming air superiority, tremendous technological prowess, phenomenal logistical backing, and plenty of big strong Americans with state of the art individual gear and assault weapons. The Americans were eager, even, ready to adopt the new counterinsurgency doctrine (called ‘COIN’) that was new and all the rage. I remember the big show my team made as we were transitioning into our sector about how we ‘wanted to get into the fight’ against the Taliban and associated anti-coalition forces and not get stuck in a quiet area.

My team and I began to make great progress in the District of Emam Sahib, an important district in Konduz Province, and we spent a lot of time there. We really were doing all of the things that ideologues hoped we’d be able to do: building protected areas, digging wells, running electricity, supporting schools for children, (especially girls’ schools), and all manner of humanitarian assistance. We even did extensive road analysis to build more optimal connectivity for the stream of agricultural products to market. All the while we’d conduct presence patrols in our gun trucks to strut safety, and the District flourished under our tutelage and torrent of money. I walked around with $50,000 U.S. in cash at all times and, trust me, it can help you make friends and influence people.

I was glad I was in charge of the team because occasionally I’d realize that not everyone had gotten the memo that we were to work within their culture and not try to simply Americanize the Afghan culture. For example, I was once on the mayor’s rooftop emplacing gun positions when I overheard an Illinois Captain pontificating to a bunch of Soldiers who were attached to me about how we should just take the Afghan Police forces and rotate them to the states one by one to train them at American Police Academies. I quickly stepped in and gave the lecture that needed to happen: dude, they’d still be coming back to Afghanistan and would have to work within myriad cultural complexities that are rooted in centuries. Let’s learn these complexities and figure out how to optimize their performance within the world that they actually live in instead.

The interpreters were a runaway exception to this rule, however. They all spoke great English, had laptops, and loved all things American. They were great to work with, very professional, and treated us very well– even insisting upon bringing me great plates of authentic Afghan food nightly when we were in the COP. Nightly. But here’s the image: every time I’d brief the Afghan and American Generals, which was daily for a good long stretch, I’d have a couple of these interpreters with me. We military would all be in military uniform, both Afghan and American, and the interpreters would be standing beside me dressed in Yankees baseball caps, Willie Nelson T-shirts, jeans and sandals. And we all just rolled with it! I always chuckled inside.

One day I was told that Prince Zahir was coming through the area and wanted to give me a feast. WTF? I learned that he was the son of the last King of Afghanistan and had seen the work we were doing for the Afghan people and so I was invited, and I could bring two people. I took my senior Sergeant, of course, but also the most junior Sergeant. The junior Sergeant was picked because he was a real gun-nut, I mean weapons aficionado, and we’d heard that the bodyguards with the Prince had some cool stuff to show us.

Back to the interpreters. One day I was with a new interpreter, who was substituting that day for one of my regulars, and we were sitting quietly outside some place, maybe waiting for something. I forget what we were doing. He struck me as a serious guy, somewhat older than the others and was plainly dressed. In the smalltalk that ensued, he told me his age and, as his enthusiasm for conversation was a bit halting, I paused. I did the math in my head and realized that he was alive during the Taliban government. Here was a guy that could speak English who could tell me what that was like! I was really excited about this rare chance to really learn something quite historic but I was patient for a few more minutes . . . and then I said quietly “What was it like?” He waited a minute, and I could see him tracing something in the dirt with a stick. Then he said, still looking down, “It used to make me sick to have to watch the stonings.” Holy shit. Oh my God. I couldn’t believe it. Then he said “Every Saturday in the middle of the village. My mom used to take me.” I said something sympathetic and respectful enough, I hope, and that was that. He’d been a child then.

So. The feast was set up outside upon a huge platform that was about four feet off the ground and the platform was covered in a gigantic exotic red Afghan rug–no doubt made for that platform. We climbed the few stairs and sat cross-legged amid the pillows and the formalities began. I was next to the Prince and his primary bodyguard was on my other side. The mayor of Emam Sahib was in attendance, as was the Police Chief. Other bodyguards were there, my guys and some others, I believe. The food was fantastic, with great piles of rice with chunks of lamb and vegetables in it, and all manner of strange little treat. This was at night and there were some kind of small torchlights positioned about strategically. The servants darted in and out of this firelight getting things and we were well attended to.

The conversation with the Prince was pretty formulaic and not very interesting. They were touring the area as a big hunting party. He liked to hunt, and must have been extraordinarily wealthy to vacation like this in the middle of a war zone while supporting a big retinue of bodyguards with state of the art weaponry. And the weaponry eventually came out for all to inspect and admire–not as an ostentatious display but because they knew my sergeants were excited about seeing the stuff. Brand new high-tech rifles, shotguns, pistols, and I guess it was the best of everything according to my guys.

And so I ended up talking to the chief bodyguard. And I’m glad I did. It turned out that he was educated in the United States, was still young, spoke perfect English, and was intelligent, articulate, and very . . . well . . . smooth. And also big, strong and very well dressed. I could see why the Prince had him as the chief bodyguard and, I’m guessing, coordinator of all his activities. This guy was very interested in talking to me. He seemed, actually, a little intent on talking to me. Talk turned from the usual pleasantries to the U.S. presence in Afghanistan. This was in 2008. He asked me finally how I thought things would go. He leaned in when he asked this, and got quiet. I wondered for a minute why he would ask such a politically sensitive question but it seemed important to him. I gave him a stock optimistic response: “we’ve got the whole coalition here, look how great it’s going in Emam Sahib, the new ‘COIN’ philosophy of military effort, etc.” . . He listened carefully and then, and I’ll never forget this in the flickering light, got a very sad and resigned look on his face. He leaned in and said “I don’t think so.”

Hmmm…. This guy was college educated in the U.S., but born and raised in Afghanistan, and, I got the feeling, probably had always traveled in the upper circles of society both here and there. I responded with some more talk, back and forth, and it was all polite and all, but then, he said it again: “I don’t think so. It’s not going to work.” Again, spoken softly and with resignation. I couldn’t believe it. Of all people, and of all the times to say this! We had so much going on in the country right then, so much money, effort, international good will. And then, alas, I realized that he didn’t believe that he was only giving me his opinion, he believed that he was teaching me something. He was telling me something out of compassion. He didn’t want me to get my hopes up. Wow. I was a little stunned. I shook it off and we got on with the rest of the feast, the pleasantries, and we said goodbye. I never saw him again.

I heard someone on the radio yesterday talking about how we’re going to try to get all of our equipment out of there but the guy on the radio didn’t even believe what he was saying and it bled through his statement. We’ve been there for 20 years and are now negotiating with the Taliban for imminent withdrawal. And I wonder. I wonder about the interpreters–all those young kids suddenly in great danger. And I wonder about the Taliban, and what they will do. I fear what they will do.

And I wonder about that guy beside me on the red rug in the firelight that night, and how he knew.

Goddammit, he knew.

He knew.

Okay, take #2 (that first one was a bit harsh).

Kevin, that was a beautiful story.

LikeLike